Consumer Engagement With Active Demand Principles and Technologies a Review

In add-on to the concepts just summarized, the literature provides models and frameworks for understanding health promotion and health research that can be helpful in the practice of community appointment. We cover a number of those here.

The Social Ecological Model of Health

The social ecological model conceptualizes wellness broadly and focuses on multiple factors that might affect health. This broad approach to thinking of health, avant-garde in the 1947 Constitution of the World Wellness Organization, includes concrete, mental, and social well-beingness (World Health Organization, 1947). The social ecological model understands health to exist affected by the interaction between the individual, the grouping/customs, and the physical, social, and political environments (Israel et al., 2003; Sallis et al., 2008; Wallerstein et al., 2003).

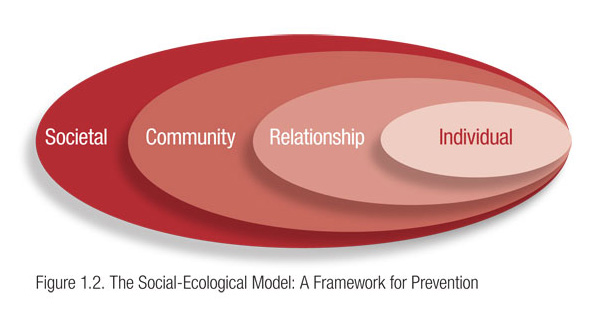

Both the community appointment approach and the social ecological model recognize the circuitous role played by context in the evolution of wellness problems equally well equally in the success or failure of attempts to address these bug. Health professionals, researchers, and community leaders can use this model to identify factors at different levels (the individual, the interpersonal level, the community, gild; encounter Effigy 1.2) that contribute to poor health and to develop approaches to affliction prevention and wellness promotion that include action at those levels. This approach focuses on integrating approaches to change the physical and social environments rather than modifying only private health behaviors.

Stokols (1996) proposes four core principles that underlie the ways the social ecological model can contribute to efforts to engage communities:

- Health status, emotional well-being, and social cohesion are influenced by the physical, social, and cultural dimensions of the individual's or community's environment and personal attributes (e.g., behavior patterns, psychology, genetics).

- The same environment may have different furnishings on an individual's health depending on a variety of factors, including perceptions of ability to control the environment and fiscal resources.

- Individuals and groups operate in multiple environments (e.g., workplace, neighborhood, larger geographic communities) that "spill over" and influence each other.

- There are personal and environmental "leverage points," such every bit the physical surround, available resources, and social norms, that exert vital influences on health and well-being.

To inform its health promotion programs, CDC (2007) created a 4-level model of the factors affecting health that is grounded in social ecological theory, equally illustrated in Figure ane.2.

The first level of the model (at the extreme correct) includes individual biology and other personal characteristics, such as age, education, income, and wellness history. The 2nd level, relationship, includes a person's closest social circle, such every bit friends, partners, and family members, all of whom influence a person'south behavior and contribute to his or her experiences. The third level, community, explores the settings in which people take social relationships, such as schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods, and seeks to identify the characteristics of these settings that touch health. Finally, the quaternary level looks at the wide societal factors that favor or impair health. Examples here include cultural and social norms and the health, economic, educational, and social policies that help to create, maintain, or lessen socioeconomic inequalities between groups (CDC, 2007; Krug et al., 2002).

The CDC model enables community-engaged partnerships to identify a comprehensive list of factors that contribute to poor health and develop a broad approach to wellness issues that involves actions at many levels to produce and reinforce change. For example, an try to reduce childhood obesity might include the following activities at the four levels of involvement:

- Individual: Conduct education programs to help people brand wise choices to improve nutritional intake, increase their physical activity, and control their weight.

- Interpersonal relationships: Create walking clubs and work with community groups to introduce healthy menus and cooking methods. Promote community gardening groups.

- Community: Work with local grocery stores and convenience stores to help them increase the amount of fresh fruits and vegetables they carry. Institute farmers' markets that have nutrient stamps so that depression-income residents can shop there. Work with the city or canton to identify walking trails, parks, and indoor sites where people can go to walk, and publicize these sites. If the area needs additional venues for exercise, build community demand and vestibule for new areas to be built or designated. Work with local employers to develop healthier food choices on site and to create other workplace health programs.

- Club: Advocate for the passage of regulations to (ane) eliminate soft drinks and high-calorie snacks from all schools, (2) ban the use of trans–fat acids in eating house food, or (3) mandate that a percentage of the budget for road maintenance and construction be spent on creating walking paths and bike lanes.

Long-term attention to all levels of the social ecological model creates the changes and synergy needed to support sustainable improvements in health.

The Active Customs Engagement Continuum

The Active Customs Engagement (ACE) continuum provides a framework for analyzing community engagement and the role the community plays in influencing lasting behavior alter. ACE was adult by the Admission, Quality and Apply in Reproductive Health (Acquire) projection squad, which is supported past the U.S. Agency for International Development and managed past EngenderHealth in partnership with the Adventist Development and Relief Bureau International, CARE, IntraHealth International, Inc., Meridian Grouping International, Inc., and the Society for Women and AIDS in Africa (Russell et al., 2008). The ACE continuum is based on a review of documents, best practices, and lessons learned during the ACQUIRE project; in a newspaper by Russell et al. (2008) the continuum is described equally follows:

The continuum consists of three levels of engagement across v characteristics of engagement. The levels of engagement, which motility from consultative to cooperative to collaborative, reverberate the realities of program partnerships and programs. These 3 levels of community engagement tin can exist adapted, with specific activities based on these categories of activity. The five characteristics of appointment are community involvement in assessment; access to data; inclusion in decision making; local capacity to advocate to institutions and governing structures; and accountability of institutions to the public. (p. half-dozen)

The experience of the Learn team shows that community appointment is not a one-time upshot but rather an evolutionary process. At each successive level of engagement, community members move closer to existence change agents themselves rather than targets for change, and collaboration increases, as does community empowerment. At the final (collaborative) level, communities and stakeholders are represented equally in the partnership, and all parties are mutually answerable for all aspects of the project (Russell et al., 2008).

Improvidence of Innovation

Everett Rogers (1995) defined diffusion equally "the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over fourth dimension amidst the members of a social system" . Communication, in turn, according to Rogers, is a "procedure in which participants create and share information with one another in social club to reach a mutual understanding" . In the instance of diffusion of innovation, the advice is about an idea or new approach. Understanding the diffusion procedure is essential to community-engaged efforts to spread innovative practices in wellness comeback.

Rogers offered an early formulation of the idea that in that location are different stages in the innovation process and that individuals move through these stages at different rates and with different concerns. Thus, diffusion of innovation provides a platform for agreement variations in how communities (or groups or individuals within communities) answer to community appointment efforts.

In Rogers' showtime phase, noesis, the individual or grouping is exposed to an innovation but lacks information nigh it. In the second stage, persuasion, the private or group is interested in the innovation and actively seeks out data. In decision, the third stage, the individual or grouping weighs the advantages and disadvantages of using the innovation and decides whether to adopt or reject it. If adoption occurs, the individual or group moves to the 4th stage, implementation, and employs the innovation to some caste. During this stage, the usefulness of the innovation is determined, and additional information may be sought. In the fifth stage, confirmation, the private or group decides whether to go on using the innovation and to what extent.

Rogers noted that the innovation process is influenced both by the individuals involved in the process and by the innovation itself. Individuals include innovators, early adopters of the innovation, the early majority (who deliberate longer than early on adopters and and so take activeness), late adopters, and "laggards" who resist change and are often critical of others willing to accept the innovation.

According to Rogers, the characteristics that affect the likelihood that an innovation volition exist adopted include (ane) its perceived relative reward over other strategies, (two) its compatibility with existing norms and beliefs, (3) the caste of complication involved in adopting the innovation, (4) the "trialability" of the innovation (i.e., the extent to which it can be tested on a trial basis), and (five) the observability of the results. Greenhalgh et al. (2004) expanded upon these characteristics of an innovation, adding (1) the potential for reinvention, (ii) how flexibly the innovation can exist used, (iii) the perceived risk of adoption, (four) the presence of a clear potential for improved operation, (5) the knowledge required to adopt the innovation, and (vi) the technical support required.

Awareness of the stages of diffusion, the differing responses to innovations, and the characteristics that promote adoption can help engagement leaders match strategies to the readiness of stakeholders. For example, a customs-engaged health promotion campaign might include raising awareness about the severity of a health problem (knowledge, the beginning stage in Rogers' scheme), transforming awareness into concern for the problem (persuasion), establishing a community-wide intervention initiative (adoption), developing the necessary infrastructure and then that the provision of services remains extensive and constant in reaching residents (implementation), and/or evaluation of the project (confirmation).

Community-Based Participatory Research

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is the most well-known framework for CEnR. As a highly evolved collaborative arroyo, CBPR would exist represented on the correct side of the continuum shown in Effigy 1.1. In CBPR, all collaborators respect the strengths that each brings to the partnership, and the community participates fully in all aspects of the research process. Although CBPR begins with an of import enquiry topic, its aim is to attain social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate wellness disparities (Israel et al., 2003).

Wallerstein et al. (2008) conducted a 2-year airplane pilot study that looked at how the CBPR process influences or predicts outcomes. Using Internet survey methods and existing published literature, the report focused on two questions: What is the added value of CBPR to the enquiry itself and to producing outcomes? What are the potential pathways to intermediate system and capacity change outcomes and to more distal health outcomes? Through a consensus procedure using a national advisory committee, the authors formed a conceptual logic model of CBPR processes leading to outcomes (Figure i.3)

The model addresses four dimensions of CBPR and outlines the potential relationships between each. The authors place:

"contextual factors" that shape the nature of the research and the partnership, and can make up one's mind whether and how a partnership is initiated. Side by side, group dynamics…interact with contextual factors to produce the intervention and its enquiry design. Finally, intermediate system and capacity changes, and ultimately, health outcomes, result direct from the intervention enquiry.

Models such as these are essential to efforts to empirically assess or evaluate customs engagement practices and disseminate effective approaches.

Translational Research

NIH has created a new impetus toward participatory research through an increment in funding mechanisms that crave participation and through its electric current focus on "translation" (i.e., turning research into practice past taking it from "the bench to the bedside and into the community"). Increasingly, community participation is recognized equally necessary for translating existing research to implement and sustain new health promotion programs, change clinical practice, improve population wellness, and reduce health disparities. The CTSA initiative is the primary example of an NIH-funded mechanism requiring a translational approach to the clinical enquiry enterprise (Horowitz et al., 2009).

The components of translational research are understood differently by different authors in the field. In one widely used schema, translational inquiry is separated into four segments: T1−T4 (Kon, 2008). T1 represents the translation of bones science into clinical research (phase 1 and ii clinical trials), T2 represents the farther enquiry that establishes relevance to patients (phase 3 trials), T3 is translation into clinical practise, and T4 is the movement of "scientific cognition into the public sector… thereby irresolute people'south everyday lives" through public and other policy changes.

Westfall et al. (2007) have identified the lack of successful collaboration betwixt community physicians and academic researchers every bit 1 of the major roadblocks to translation. They annotation that although the majority of patients receive well-nigh of their medical care from a physician in a community setting, most clinical enquiry takes place in an academic setting (Westfall et al., 2007). Consequently, the results of clinical trials may not be easily generalized to real-globe clinical practices.

One solution to this dilemma is practice-based research (PBR): engaging the practise customs in research. PBR has traditionally been conducted in a primary care setting using a coordinated infrastructure (physicians, nurses, and office staff), although the recent emphasis on translation has contributed to the emergence of more specialized practice-based research networks (e.g., in nursing, dental care, and pharmacy). Similar all efforts in engagement, developing PBR includes edifice trust, sharing determination making, and recognizing the expertise of all partners. PBR addresses iii particular concerns almost clinical do: identifying medical directives that, despite recommendations, are non being implemented; validating the effectiveness of clinical interventions in community-based primary care settings; and increasing the number of patients participating in show-based treatments (Westfall et al., 2007). "PBR also provides the laboratory for a range of research approaches that are sometimes better suited to translational inquiry than are clinical trials: observational studies, physician and patient surveys, secondary data assay, and qualitative research" (Westfall et al., 2007, p. 405).

Source: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_models.html

Post a Comment for "Consumer Engagement With Active Demand Principles and Technologies a Review"